From the Toolbox: The Validation Gap — Why Most Inventors Fail Between Idea and Proof

Most inventions do not fail because they are bad ideas.

They fail because they never survive validation.

Between concept and credibility lies what I call the Validation Gap — the space where enthusiasm collapses under uncertainty, cost anxiety, and methodological drift. This is the zone where most independent inventors stall, not due to lack of intelligence or creativity, but due to lack of structure.

Institutions solve this with departments, committees, and capital buffers. Independent inventors don’t get those luxuries. That is precisely why validation must be engineered, not improvised.

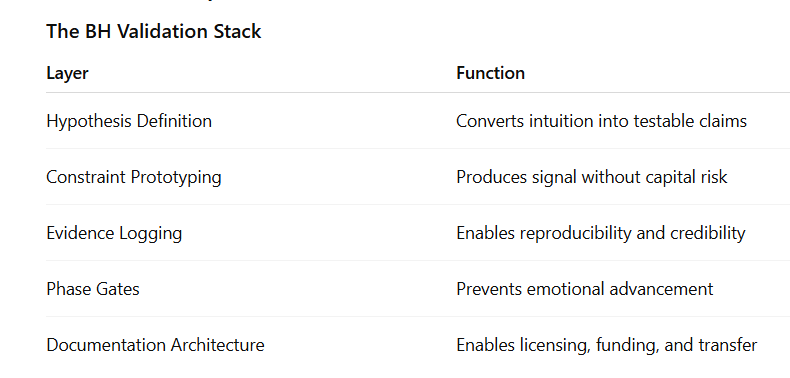

The BH Methodology was built to close this gap.

The Real Enemy: Informal Progress

Most inventors operate under what I call informal momentum:

Sketches without test criteria

Prototypes without hypotheses

Feedback without measurement

Spending without decision gates

Progress feels real — until it isn’t. The invention advances emotionally but not evidentially. And when funding conversations, patent filings, or manufacturing questions arise, the project collapses under its own undocumented weight.

Validation is not inspiration.

Validation is evidence under constraint.

Phase 1: Hypothesis Engineering

Before anything is built, a claim must be defined:

“This system will achieve X performance under Y conditions using Z constraints.”

Without a falsifiable hypothesis, prototypes become sculptures instead of instruments.

BH Principle:

Every build must exist to answer a question — not to express an idea.

Phase 2: Constraint-First Prototyping

Institutional labs scale resources to problems. Independent inventors must scale problems to resources.

This means:

Testing single functions instead of full systems

Using surrogate materials instead of final-grade components

Validating failure modes before optimizing success paths

Constraint-first prototyping does not slow innovation — it accelerates truth.

The objective is not elegance.

The objective is signal extraction.

Phase 3: Evidence Capture, Not Impressions

Most inventors remember what felt promising.

Professionals record what measured promising.

Validation requires:

Logged variables

Controlled changes

Reproducible outcomes

Version tracking

A prototype that produces undocumented insight is functionally identical to a prototype that produced none.

If it cannot be audited, it cannot be trusted.

If it cannot be trusted, it cannot be scaled.

Phase 4: Phase-Gate Decisions

Momentum is dangerous without gates.

The BH Methodology uses phase-gate logic, meaning:

You do not proceed because you are excited.

You proceed because criteria were met.

Each phase must answer:

What question was tested?

What evidence was produced?

What risk was retired?

What uncertainty remains?

If these cannot be answered, the project does not advance — regardless of how compelling the idea feels.

This is not conservatism.

This is capital protection.

Why Institutions Win (And Why Independents Can Too)

Universities, corporations, and government labs dominate innovation not because they are smarter — but because they control validation pathways.

They standardize:

Testing protocols

Documentation formats

Review thresholds

Funding gates

Independent inventors can outperform institutions — but only if they adopt institutional-grade structure without institutional overhead.

That is what the BH Methodology exists to do.

The Bottom Line

Invention does not fail at ideation.

It fails at transition — between belief and proof.

The Validation Gap is not a creativity problem.

It is a systems problem.

And systems can be engineered.

If you want your ideas to survive contact with reality, funding conversations, patent offices, manufacturers, and markets — then validation must stop being emotional and start being architectural.

That is not bureaucracy.

That is leverage.

Validation is not proof of brilliance.

It is proof of discipline.

And discipline is what scales.

— TS Blackwell-Hart